In Chinese culture, the tradition of yuezi (月子) or the practice of postpartum care for the mother is a longtime established practice. In Taiwan’s case, this practice underwent and continues to undergo the vicissitudes of social and interpersonal relationship changes. Before the 1970s, the birth rate in Taiwan was very high and the idea of "more children, more grandchildren, more good fortune" (多子多孫多福氣) was widely accepted. The large family size also meant sufficient human resources for the agricultural-related field labor. The practices of yuezi were already crucial at that time and mothers in the postpartum period had some privileges like a long rest and special food (particularly meals containing meat like chicken, a precious food at that time). The importance of yuezi could be partly explained by the high mortality of mothers and babies during childbirth and there was thus a traditional Taiyu proverb saying that “If you survived delivery, you enjoy the smell of chicken in sesame oil and if you did not, you have only four wooden boards [a coffin].” (生得過,雞湯香;生不過,四塊板。) The main goal of yuezi was the mothers’ recuperation of physical force in order to restart the domestic and field work on the one hand, and the restoration of women’s reproductive capacity on the other. However, the modernization of the country caused huge changes in social arrangements, including the reduction of family size and the advent of small nuclear families, the influences of Western medicine and social organization based upon individualism, and the drastic drop of fertility rates. Accordingly, the practices of yuezi underwent important changes, both in terms of yuezi-related behavior and also in the conception of this tradition. The apparition of yuezi centers (月子中心) is doubtlessly one of them.

Taiwan is a pioneer in the institutionalization of the yuezi practice through yuezi centers. Indeed, postnatal care centers first originated in Taiwan at the end of the 1990s, where they combined childbirth with postpartum care and were legalized by public health authorities. After that, the model of the postpartum care center was borrowed by mainland Chinese companies and began to appear in Beijing and Shanghai, developed throughout China and spread even in North America to meet sinophone global citizens’ needs. Thus, the practice of attending a postpartum care center becomes common and popular in Taiwan, and about 60% of Taiwanese mothers (compared to 5% in China) go to one of those centers after giving birth. More concretely, there are two kinds of postnatal care centers in Taiwan. The “yuezi centers” (月子中心) are managed by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and only require business registration. They are a kind of special “pension” where mother and newborn stay and repose for about two to four weeks. There is no medical professional in these centers, but most of the yuezi centers employ experienced staff with babysitting or domestic helping qualifications to provide care and service for mothers and babies. Those centers are registered under the name of “yuezi centers” or “yuezi club.” The other institution is the postpartum nursing care home (產後護理之家) in which there is professional nursing staff who provide professional nursing care services, including daily life care and guidance on wound recovery, newborn care, breastfeeding, etc. These institutions must apply for a business license in accordance with the relevant strict regulations of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and must be annually accredited. While, according to related legal regulations, there should be at least one medical professional for every fifteen beds (including beds for mothers and babies), many institutions, under competition pressure, offer one professional caregiver for every five beds. Some institutions even underline their better-than-average ratio of clients/professional helpers (namely one professional for every four babies) in their advertisements. Another determinant difference between yuezi centers and postpartum nursing care institutions is that the latter should be attached and supported by a hospital. As a result, in general, their names are mostly “postpartum care homes” and “postpartum nursing care homes attached to (name of the hospital).”

It is not surprising that the stay in these highly medicalized and specialized institution is very expensive, particularly in the Greater Taipei area. The price ranges from 7000 NTD (220 Euros) to 20000 NTD (620 Euros) every day in central Taipei. Furthermore, the trend of fewer children has not affected the growth of these institutions, on the contrary, postnatal market competition is becoming increasingly fierce. This is because shrinking family sizes have increased the resources available for each child and intensified parents’ investments in both sons and daughters.¹ For families having fewer children, offspring become more “precious”² because they are rare, but also because of the economic and emotional investment that parents make in them.

It is also worth emphasizing that there is a growing government-involving in this de-privatization of postpartum care. For example, in Kaohsiung, the second- biggest city in Taiwan, in order to encourage childbirth, which is constantly decreasing, the local government is the first in the country to introduce a new series of pregnancy-friendly measures. These include the “postnatal care at home” service, which provides postpartum care by experienced helpers and skilled professionals. For the first child, parents are offered with a subsidy of 100 hours of postpartum care; for the second newborn, 160 hours; and for the third and subsequent newborns, 240 hours. If the number of hours exceeds the subsidy, the remainder will be purchased from the trustee at the rate of NT$250 (about 8 Euros) per hour.³ This could be seen as a social innovation introduced by both government and caregiving industry, deepening the transition of postpartum care from families to health professionals.

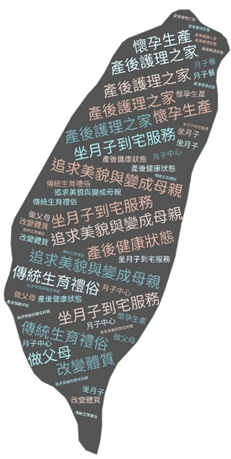

In fact, this hybridity and pluralization of postpartum care is an illustrating example of what sociologists call “compressed modernity”.⁴ “Compressed modernity” is a civilizational condition in which economic, political, social and/or cultural changes occur in an extremely condensed manner in respect to both time and space, and in which the heterogenous coexistence of mutually disparate historical and social elements leads to the construction and reconstruction of a highly complex and fluid social system. For example, in modern Taiwan, Confucianism and the discourse of filial piety are still strong, while at the same time neoliberal individualism and Western feminism penetrates public and private spheres. Thus, behind the reason for “life is precious, and babies are priceless”, there is a strong need to professionalize infant care and child education and a parental wish to invest in their children from the very beginning, with new technologies and new parenting discourse coming from the West. Therefore, perinatal care centers represent an important and pioneer shift in the social practices, moving from the management of the perinatal period by the private sphere (often the husband’s family, involving mothers-in-law and other female family members) to institutions’ taking over, such as perinatal care centers, involving doctors, nutritionists, medical professionals, yoga teachers and other experts of childcare. In this intersection between local traditional ideas and new institutionalization of postpartum care, women and their families’ yuezi-related behavior will be adjusted with personal touch in order to strike a balance between tradition and modernity. For example, the taboo of not reading after childbirth is mostly not followed, while the taboo of not washing hair or taking a bath after childbirth is sometimes chosen to be followed with new products like water-free bathing lotion to achieve a compromise. However, meeting two competing discourses of yuezi is never easy, and mothers are often confronted with incompatible demands in their everyday lives. This situation also causes many intergenerational tensions, due to the different interpretation of the meaning of “good” postpartum care.⁵ These are some of the inevitable prices of “compressed modernity.” In this endless interplay between tradition and innovation, typical to “compressed modernity,” there are not only the above-mentioned shifts from the private space to institutionalization, but also expanding belief and confidence in expert knowledge. Regarding the choice of these postpartum institutions, mothers and their families hold that “quality of care provided by the medical team” was the most important factor, often followed by the “infant and professional caregiver ratio” as the main concern. Moreover, the purpose of the postpartum care has changed from emphasizing potential changes of mothers’ physical constitution after childbirth (改變體質) to restoring and maintaining the pre-pregnancy state.

Another huge change is that the child-centered emphasis and priority of mother and infants’ health in traditional yuezi now coexist with the working mothers’ personal desires and professional needs. The keyword of “sacrifice” for children in the traditional gendered expectation is replaced by multidimensional considerations and individual concerns, since women need to maintain paid work, and divorce is becoming frequent in present-day Taiwan.

Finally, an important difference is the recent promotion of the “yummy mummy” or the “new sexy Mom” by mainstream media slimming advertisements. In fact, previously there was no such thing as “bouncing back” after childbirth for older mothers, while the imperative of “getting your body back” is gaining popularity and fervency in contemporary Taiwan.⁶ Under the pressure of intensive mothering, modern women are complex subjects who are influenced by multiple and conflicting norms. Mothers’ concern about their babies often competes tremendously with anxieties about appearance; but caring about their pregnant and postpartum appearance does not erase women’s concerns about the well-being of their babies, and there are multiple social demands on these new mothers.

Taiwan’s pioneering social invention increasingly becomes a global phenomenon. For example, the loosening of the one-child policy and the recent introduction of the second and third child policy in mainland China has triggered a period of growth for postpartum clinics and postpartum food industry. In the USA, there is already an important penetration of similar postpartum nursing institutions, especially on the West Coast, due to the important numbers of “Chinese people” (華人). Yet, with the increase of Taiwanese and Chinese mothers who chose to give birth abroad in order to give their children the asset of a North American citizenship, these institutions begin to flourish everywhere in the USA. It is of interest to pay attention to the various consequences of this de-privatization and professionalization of postpartum care. Although new Taiwanese mother and their families are provided with expertise and professional care in these institutions, many family ties and interpersonal relationship are also profoundly changed. At these centers, mothers often receive standardized sets of services, and because of the commercialization of yuezi, women face a rationalization and alienation of social space and interpersonal relationships during the consumption of professional postpartum care. This system of combined commercialization and medicalization renders postpartum care “impersonal,” which implies the loss of the aspect of interfamilial emotions and mutual care. While some celebrate that an isolated space in a public institution helps to keep unwanted visits and some troublesome family members away from the mother-baby cocoon, many women recall the nostalgia of privileged postpartum period where mothers received many female family members’ devotedness, full of tenderness and mutual trust. In sum, it is relevant to examine manifold contexts and various consequences of this professionalization of postpartum care and how mothers try hard to negotiate and compromise different discourses about “doing the month.”

[1] Yu & Su (2006).

[2] Paltrinieri (2013).

[3] For more detail see Gaoxiong shi shehuiqu (2022).

[4] Chang (2010).

[5] Keyser-Verreault (upcoming).

[6] Keyser-Verreault 2018a, 2018b, 2021.

Chang, Kyung-Sup (2010). South Korea Under Compressed Modernity: Familial Political Economy in Transition. London: Routledge.

Gaoxiong shi shehuiju 高雄市社會局 (2022). ”Zuo yuezi daozhai fuwu” 坐月子到宅服務, https://khchildcare.kcg.gov.tw/cp.aspx?n=93523EF8385CFF39 [last accessed 12-02-2022].

Keyser-Verreault, Amélie (upcoming). “On ne naît pas belle, on le devient: devoir maternel et formation transindividuelle de l’entrepreneure esthétique à Taiwan” (One is not born beautiful, one becomes beautiful: Motherly duty and transindividual transformation of the esthetic entrepreneur in Taiwan), in: Famille, Enfance, Génération.

Keyser-Verreault, Amélie (upcoming). “The continuum of getting the body back: Procreative choice and changing maternity under beauty culture in Taiwan”, in: European Journal of Cultural Studies.

Keyser-Verreault, Amélie (upcoming). “Toward a Non-Individualistic Analysis of Neoliberalism: The Stay-Fit Maternity Trend in Taiwan”, in: Ethnography.

Keyser-Verreault, Amélie (2020). “‘I want to look as if I am my child’s big sister’: Self-satisfaction and the Yummy Mummy in Taiwan.”, in: Feminism and Psychology, 31: 4, 483–501.

Keyser-Verreault, Amélie (2018a). “Huifu zixin meiti: meixue jingying zhuyi xia de muxing zhuti yu huaiyun shengchan”「恢復自信美體」:美學經營主義下的母性主體與懷孕生產 (Recovering a self-confident body: Pregnancy and childbirth under aesthetic entrepreneurship), in: Journal of Women’s and Gender Studies (女學學誌), 43(2), 37–88.

Keyser-Verreault, Amélie (2018b). “Zhuiqiu meimao yu biancheng muqin de liang nan: yi gao wenping de duhui nüxing wei li” 追求美貌與變成母親的兩難:以高文憑的都會女性為例 (Quest for beauty and becoming a mother: A painful paradox for highly educated urban Taiwanese women), in: Taiwan Journal of Anthropology (台灣人類學刊), 16(1), 97–158.

Paltrinieri, Luca (2013). “Quantifier la qualité: Le capital humain entre économie, démographie, and éducation”, in: Raisons politiques, 4(52), 89–107.

Yu, We-Hsin and Su, Kuo-Hsien (2006). “Gender, Sibship Structure, and Educational Inequality in Taiwan: Son Preference Revisited”, in: Journal of Marriage and Family, 68 (4), 1057–1068.